You are here:

- CMP Home >

- Web Exhibits >

- Stereoscopic Images >

- Pennsylvania

- SUBJECT:

- COMPANY:

- GEOGRAPHIC LOCATION

Stereoscopic Images of Cleveland in 3-D

Pennsylvania

- This gallery contains 9 slides. Click on the arrows to advance to the next or previous slide.

- Click on the the photo to see the 3-D rendering.

- To view the total effect of the 3-D versions of the images use anaglyph 3-D Glasses (red/cyan).

-

Shooting an Oil Well with Nitroglycerin, Penna.

The word petroleum means "rock oil," or oil that comes from the ground. Far down in the earth, sometimes as far as 4,000 feert, petroleum is stored in sands which lie between layers of rock through which the oil cannot escape. We need that oil because from it are made gasoline, lubricating oils, and other products. This well has been drilled, and the driller found, by examining the dirt brought to the surface by his machine, that oil was near. The he lowered a can of nitroglycerin into the well. You know that nitroglycerin is a very powerful explosive. In the top of the can was a torpedo. A weight called a go-devil was next dropped upon the can. The torpedo exploded and ignited the nitroglycerin. A terrific explosion followed. You see the result. The oil was forced up the well and shot high into the air! That derrick is 72 feet high and the streem or oil is much higher.

This well should now yield oil for some time. If the pipe becomes clogged with paraffin, it may be torpedoed again. If such and explosion does not start a flow of oil, the dirller must either drill deeper or drill in another place.

Most petroleum is dark green in color. Some of it is thick as syrup, some is like kerosene. All crude oil must be refined before it becomes gasoline. From the storage tanks near the weeksm it is carried away in tank cars or is driven by pumps through pipes to refineries. These pipe lines are laid under rivers, through mountains, under out very feetm for hundreds of miles. In the refineries, pertoleum is heated and different products are obtained, of which the most important and valuable is gasoline. -

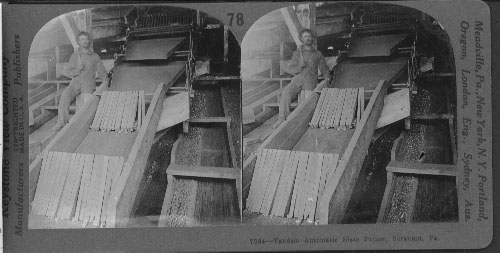

Tandem Automatic Slate Picker, Scranton, Pa.

Unless you know something of the history of coal mining, you cannot understand the value of the machine here shown. In the great breaker building the coal is first crushed. But the coal is not pure. There are minerals, especially slate, mixed with it. This must be removed before the coal is put into the cars for shipment. The labor of sorting out these pieces of slate and rock was formerly given over to boys. These were only lads of from 9 to 15 years, who sat all day long beside the small coal chute, working for a small sum of money per day. Here they sat, cramped and stooping, their little hands worn and tired, and their bodies aching.

You perhaps have heard of the term, child labor. Much has been written and said about it in the last few years. Every child should be given a chance to make the most of himself. In his youth he should be given an opportunity to learn about the things that other people do, and how they do them. Then, when he grows to manhood, he will be able to decide upon a business which he thinks he will like. The breaker boy had no chance to do this. Now laws have been passed to prevent children under a certain age, from working all day long.

Moreover, machines have been invented that make labor unnecessary in coal mining. The simple one you see here does the work of many breaker boys. As the coal slides down these chutes, the wooden jigs lift and let the lighter, fast-traveling coal pass by, but hold the heavier slate and rock. The machine is not at work, as you see it, but under each of the jigs is shown a pile of slate that had been caught. This slate is dropped into special chutes and removed from the breaker. -

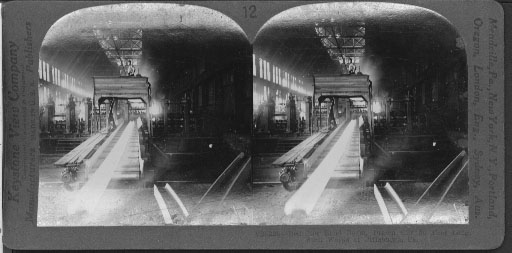

Red Hot Steel Beam, Drawn Out 90 Feet Long, Steel Works at Pittsburgh, Pa.

Pittsburgh, Pa., is the greatest steel producing city in the whole world. This picture shows a portion of the interior of one of the great steel mills. The iron is sent direct from the mine to the furnace stock pile. These are rooms in these great steel works where the iron ore and scrap iron are melted and transformed into fiery liquid. When this melted iron is drawn off it is about as thick as mild, and is called pig iron. This pig iron is the basis of all steel manufacturing. The liquid iron is then taken in huge ladles by means of electric cranes to converters or mixers. Here it is mixed with carbon of tungsten, or whatever is necessary to give the desired character to the steel. Then heavy ladles are filled with this substance and swung out over ingot moulds. The liquid steel is run into these, and freezes (way above the boiling point) into the desired shape. In the room steel rails are being made. This white, dazzling beam of metal had been rolled out to a length of about ninety feet. From this point it will be carried on rollers to a cutting platform, where it will be sawed into the proper lengths, then sent through a straightening department where the ends will be squared and the holes punched for the fishplates. It is then ready to be shipped.

The rails are loaded by a crane which is itself a huge electro-magnet. This picks up a load of steel rails as easily as a small magnet picks up a cluster of needles. -

Stripping Anthracite Coal, Penna.

When a vein of coal lies near the surface of the earth it is mined in the way shown in this picture. All the dirt on top of the coal is removed by big steam shovels, one of which you can see at work. The dirt so removed is called strippings. The machines which do this work weigh almost fifty tons and remove strips of earth about twenty-five feet wide and ten feet deep. The stripping is hauled away in small cars. Notice that more earth had been removed in the center of the view. There the vein of coal is uncovered and can be taken out from the top. All that great hill of earth on the left must be cleared away, but great as the work is, it is cheaper to do it than it is to sink shafts into the ground and do the mining underground.

By the stripping method all the coal can be mined, but in mining from shafts supports of coal must be left at certain distances apart to hold up the ceiling. Mining from shafts, sunk from the surface of the earth downward, or into the side of a hill, is the more common way of coal mining because most coal is not near enough the surface to be reached by the stripping method.

Which method of mining do you think the miners prefer?

Where are the anthracite coal mines of this country? -

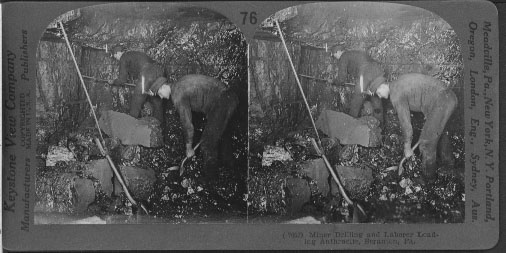

Miner Drilling and Laborer Loading Anthracite, Scranton, Pa.

Here you see a miner and his helper working in a coal mine. The miner contracts with the company to mine the coal for so much per car or per ton. He furnishes his own tools, pays for the powder with which to blast the coal loose, and hires a helper to assist him at so much a day or so much per ton.

The miner in the background is drilling a hole in the solid layers of anthracite, making ready to put in a blast of powder. The helper is busy shoveling the loose coal into a car which will carry it to the elevator. From there it will be taken to the surface where there is a coal breaker. You will observe that each man has a tin lamp fastened to the front of his cap. What looks like candles sticking up from these lamps are the sheets of flame.

This scene was taken with a flashlight, so the mine appears to be very well lighted. As a matter of fact, it is pitch dark in here. The lamps from the miners' cap make just enough light to cast queer-looking shadows in all the corners. How would you like this kind of work, far below ground in the dark?

Anthracite is the coal we call hard coal. The soft coal is called bituminous coal. The anthracite district of the United States is a small area, and Scranton is in the very heart of it. Soft coal is found in many states. Pennsylvania leads in the production of both kinds. In the United States, but little anthracite is found outside of Pennsylvania. West Virginia, Illinois, Ohio, Kentucky, Indiana, and Alabama are our most important producers of soft coal. The value of bituminous coal in the United States in 1915 was over $500,000,000. The value of the anthracite was $185,000,000. -

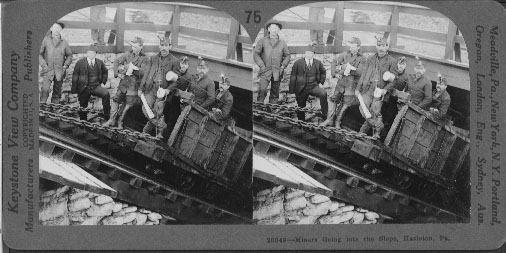

Miners Going into the Slope, Hazleton, Pa.:

You see here a crowd of miners on a car ready to be lowered into a Pennsylvania coal mine. Inside the shaft, running directly down into the earth, there is a tunnel, or slope, as it is called, leading into the mine. On cats such as the one here shown coal is brought to the surface from far back in the mine. A stationary engine furnishes the power to drag the cars up the steep incline.

The scene is rich in suggesting the life of coal miners. On top of the caps of the men are lamps, some of which are already lighted. Oil is burned in these little tin lamps. One of the miners has on rubber boots, because there may be water in certain parts of the mine. Most of the men seen here are foreigners. The overseer or "boss" of the mine is easy to find.

If you were to go with these miners you would likely find that the slope was built through a vein of coal. Sometimes, however, the vein is tapped by cutting through dirt and rock. At any rate, when the slope comes to the coal vein, it winds about in the heart of the vein. Leading off from either side of it are long tunnels in which switches have been built so that the cars can be run off to the various rooms and there loaded.

The life of these miners is not east. They are well paid, the amount they receive annually depending on the amount of coal they mine. But it is lonely work. All day long, with drill, pick, and shovel, they labor steadily. Sometimes an accident happens. Gases form in some of the mines, and these are set on fire by the lights on the miners' caps. An explosion occurs. Sometimes many miners are cut off far below ground. Rescue parties may work for days in an attempt to save their lives. -

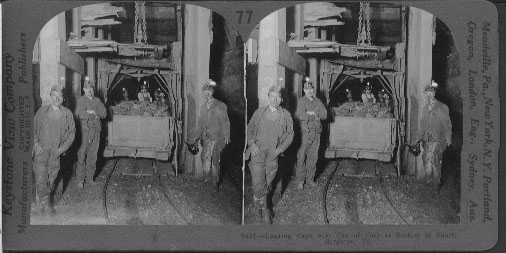

Loading Cage with Car of Coal at Bottom of Shaft, Scranton, Pa.

Here you are at the bottom of an anthracite, or hard coal mine. This is the lower end of the large shaft which leads to the surface of the earth perhaps 1,500 feet above. A carload of coal is on the elevator or cage ready to be lifted to the top of the dump into the breaker. The cage and the shaft are the center of a mine of this kind. To it lead the many switches from acres of underground rooms. It is necessary that this shaft be constructed of strong materials. For not only must all the coal be brought to the surface through it, but it is the only exit of the hundreds of miners.

You can see for yourself that the shaft and cage here shown are strongly made. You will observe the large timbers, the heavy framework of the cage, and the big safety chain above. The weight on the cage you can figure for yourself. The car weighs one ton and the coal two tons. The cage weights 1 1/2 toms and the 1500 feet of wire rope, which lifts it, another 1 1/2 tons. How much is this in all? You will be interested to know that the rope is made of strands of woven steel wire, 19 wires to the strand. It is 1 1/8 inches in diameter and can lift a weight of 60 tons. Some of the cages used in these mines have two decks, one about the other. By this means, two cars of coal can be lifted at a time.

Some of the Pennsylvania shafts are sunk 3,000 feet beneath the surface of the earth. This means that some of the coal is actually mined below sea level. In many of these deep mines it is necessary to have extensive pumping equipment to remove the inflow of water. Pennsylvania mines, however, are shallow as compared with most of those in Europe. Some of the European mines are over a mile in depth. -

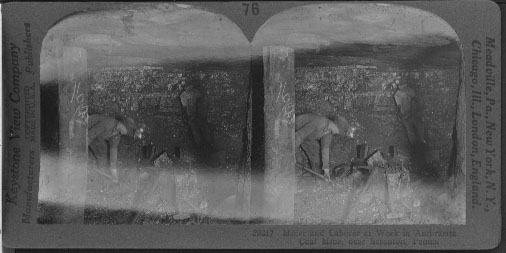

Miner and Laborer at Work in Anthracite Coal Mine, Scranton, Pa.

No accompanying text available.

3D version not available. -

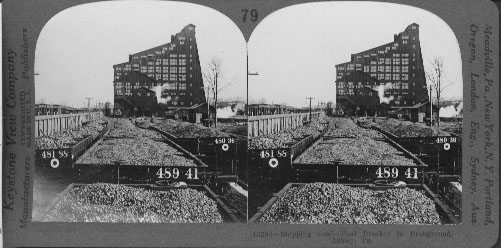

Shipping Coal —Coal Breaker in Background, Ashley, Pa.

CARLOADS OF COAL WITH BEAKER IN THE BACKGROUND, ASHLEY, PA: The big building in the background looks somewhat like a great grain elevator on the plains. It is a coal breaker. It gets its name from the fact that in this building coal is broken into usable sizes. It is necessary to break the coal because it comes from the mine in uneven lumps, some of which are very large.

A breaker is built near the mine shaft so that the small coal cars can be lifted directly from the bottom of the mine to the top of the breaker. Here the large pieces are broken, and as the coal travels downward it is sorted and sifted into its many grades. This is done in the modern breakers by machinery. If you were to ask your coal dealer about the different kinds of coal he would name them according to the size of the lumps. Rice coal is the siftings, the very small pieces. Buckwheat coal is the next size. Then come in order, pea coal, chestnut coal, stove coal, egg coal, and grate coal. There is still a larger variety known as steamboat coal, but this is too large to be burned in an ordinary furnace.

The sorting of these different kinds of coal is done by a system of screens which lie in tiers. Each succeeding screen projects farther out than the one next above it. The finest coal falls into the first row of bunkers, the next in order falls into the next row of bunkers, and so on.

As you see, switches from the railroad are connected with the breaker. The coal falls into car from chutes leading from the breaker. One of these chutes you can see at the left of the breaker building. You will observe that each car is loaded with the same size lumps. These cars carry the fuel that heats our houses, lights our cities, drives our street cars, and runs the machinery of industry.

This tonnage was estimated to be about $1,012,829,000.